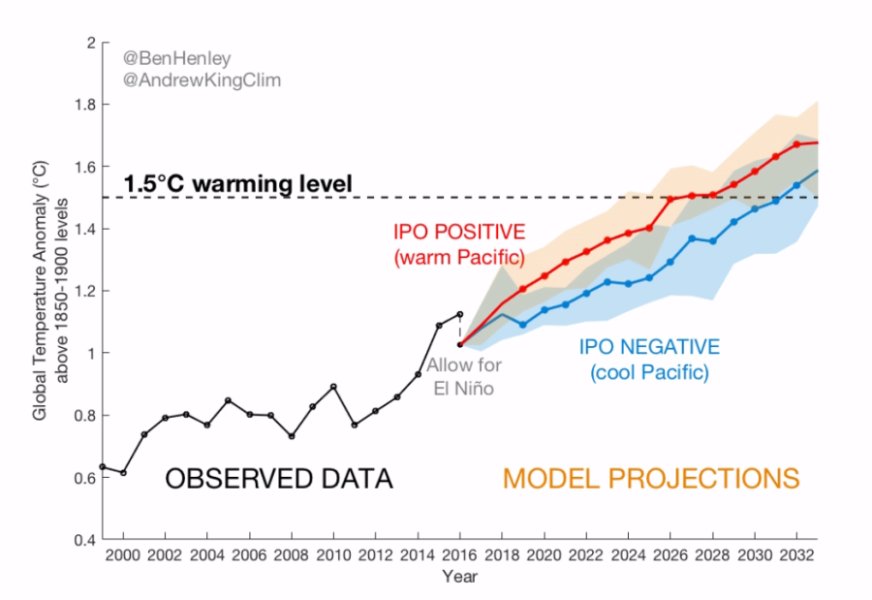

Die University of New South Wales zeigte sich am 8. Mai 2017 scheinbar progressiv und veröffentlichte eine Temperaturprognose für die kommenden 15 Jahre unter Einbeziehung von Ozeanzyklen:

Abbildung 1: Temperaturprognose von Henley & King 2017 für die kommenden 15 Jahre.

Das Fehlen der Ozeanzyklen in den Klimamodellen und Temperaturprognosen ist ein Hauptkritikpunkt in der derzeitigen Klimadiskussion. Ein näherer Blick auf die Vorhersage und Begründung bringt jedoch Ernüchterung. Die gebremste Erwärmung der letzten anderthalb Jahrzehnte wird zwar korrekt in der Graphik dargestellt, allerdings wird der El Nino 2015/16 dann als Endpunkt der Entwicklung interpretiert, auf den eine steile Erwärmung folgt. Dabei wird zwischen zwei Zuständen der Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO) unterschieden, die leichte Unterschiede im Temperaturverlauf bringen sollen.

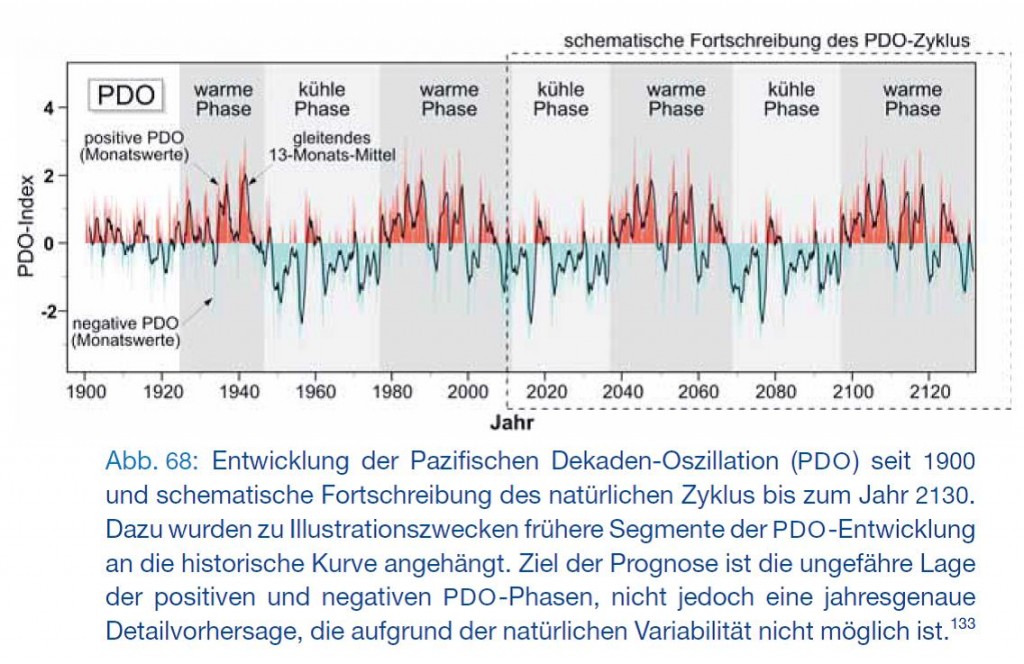

In Wahrheit sollte jedoch die PDO (Pazifisch Dekadische Oszillation) hier eine viel wichtigere Rollen spielen. Und die PDO wird aller Voraussicht nach noch bis weit in die 2030er Jahre in der negativen also kühlenden Phase sein. In unserem Buch „Die kalte Sonne“ haben wir eine PDO-Prognose vorgestellt, die eine simple Fortschreibung der bisherigen PDO-Zyklik annimmt:

Abb. 2: PDO-Prognose aus Vahrenholt & Lüning (‚Die kalte Sonne‘).

Die von Henley & King 2017 vorgeschlagenen Auswirkungen der Ozeanzyklen sind daher schwer nachzuvollziehen und eher unwahrscheinlich.Vermutlich verwechseln die Forscher auch die Auswirkungen des El Nino mit den Ozeanzyklen. Zum Glück können wir die Mittelfrist-Prognose in den kommenden Jahren mit der Realität überprüfen, so dass wir uns hier weitere Spekulationen ersparen können. Anbei noch die Pressemitteilung der University of New South Wales zur Prognose, die sich leider hochpolitisch und alarmistisch liest:

Paris 1.5°C target may be smashed by 2026

Global temperatures could break through the 1.5°C barrier negotiated at the Paris conference as early as 2026 if a slow-moving, natural climate driver known as the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation (IPO) has, as suspected, moved into a positive phase.

New research published in Geophysical Research Letters by University of Melbourne scientists at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science shows that a positive IPO would likely produce a sharp acceleration in global warming over the next decade. Since 1999, the IPO has been in a negative phase but consecutive record-breaking warm years in 2014, 2015 and 2016 have led climate researchers to suggest this may have changed. In the past, these positive phases have coincided with accelerated global warming. „Even if the IPO remains in a negative phase, our research shows we will still likely see global temperatures break through the 1.5°C guardrail by 2031,“ said lead author Dr Ben Henley. „If the world is to have any hope of meeting the Paris target, governments will need to pursue policies that not only reduce emissions but remove carbon from the atmosphere.“ „Should we overshoot the 1.5°C limit, we must still aim to bring global temperatures back down and stabilise them at that level or lower.“

The IPO has a profound impact on our climate because it is a powerful natural climate lever with a lot of momentum that changes very slowly over periods of 10-30 years. During its positive phase the ocean temperatures in the tropical Pacific are unusually warm and those outside this region to the north and south are often unusually cool. When the IPO enters a negative phase, this situation is reversed. In the past, we have seen positive IPOs from 1925-1946 and again from 1977-1998. These were both periods that saw rapid increases in global average temperatures. The world experienced the reverse — a prolonged negative phase — from 1947-1976, when global temperatures stalled.

A striking characteristic of the most recent 21st Century negative phase of the IPO is that on this occasion global average surface temperatures continued to rise, just at a slower rate. „Although the Earth has continued to warm during the temporary slowdown since around 2000, the reduced rate of warming in that period may have lulled us into a false sense of security. The positive phase of the IPO will likely correct this slowdown. If so, we can expect an acceleration in global warming in the coming decades,“ Dr Henley said. „Policy makers should be aware of just how quickly we are approaching 1.5°C. The task of reducing emissions is very urgent indeed.“

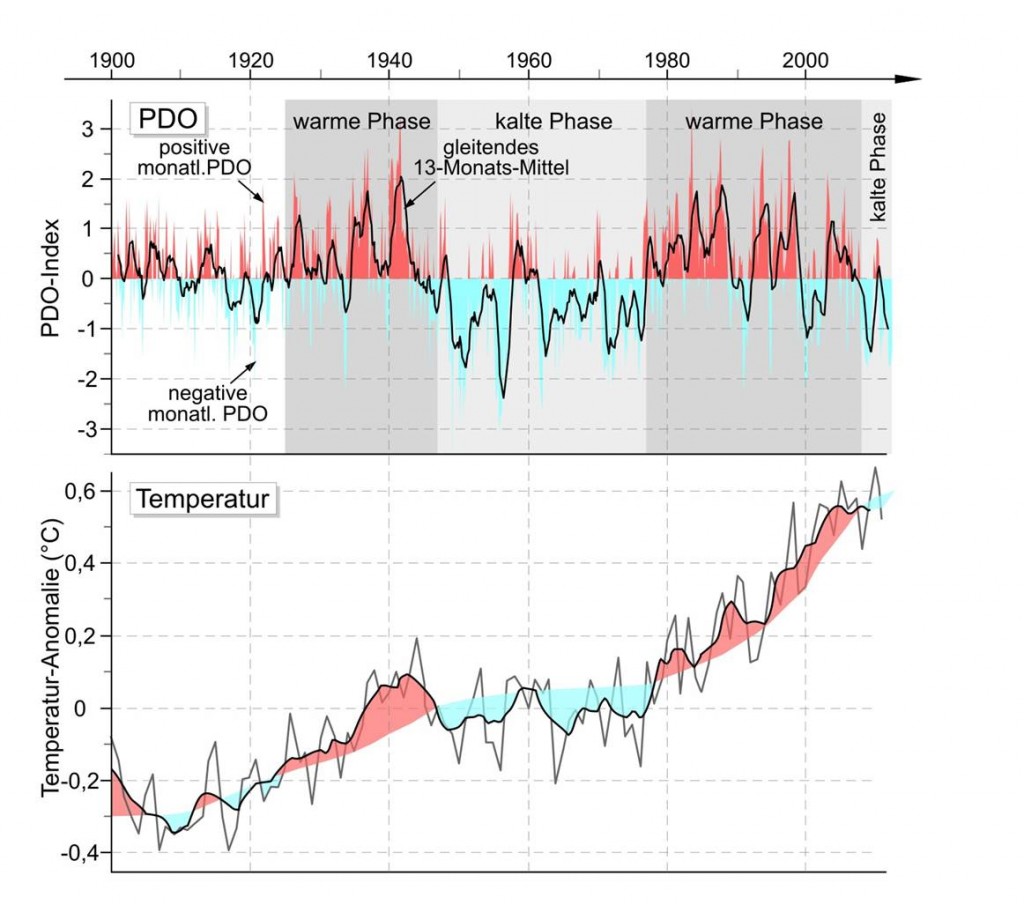

Und so hat die Natur in der Vergangenheit wirklich auf die pazifschen Ozeanzyklen reagiert:

Abb. 3: Negative PDO-Phasen führten in der Vergangenheit zu mehrjahrzehntigen Erwärmunsgpausen. Derzeit beginnt eine weitere negative PDO-Phase. Abbildungsquelle: Vahrenholt & Lüning (‚Die kalte Sonne‘).

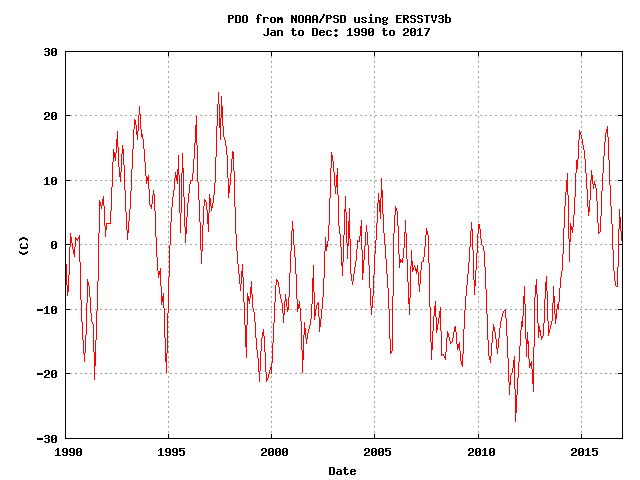

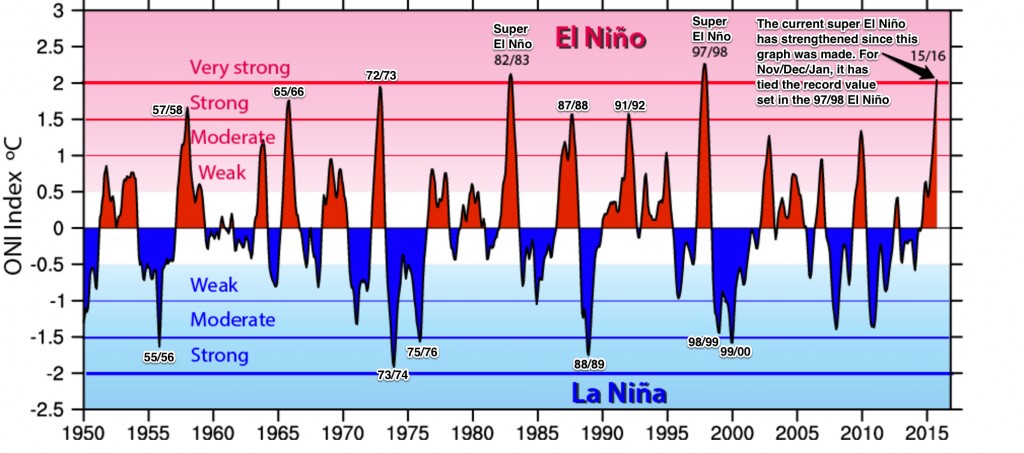

Wie gestaltet sich der Übergang von der positiven PDO-Phase 1975-2010 zur negativen PDO-Phase? Dazu zoomen wir uns in die letzten 25 Jahre der PDO hinein (Abb. 4). Der allgemeine PDO-Abstieg zwischen 1990 und 2013 ist gut zu erkennen. Der El Nino 1997/98 produzierte eine schöne PDO-Spitze, genau wie der El Nino 2015/16 (Abb. 4, 5). Es ist davon auszugehen, dass die derzeit fallenden PDO-Werte bald wieder dauerhaft im negativen Bereich liegen und sich die negative PDO-Phase damit entwickelt wie erwartet. Die beobachteten El Nino-Unterbrechungen stellen keinen Grund dar, am generellen Verlauf zu zweifeln.

Abb. 4: PDO-Verlauf von 1990 bis April 2017. Quelle: NOAA.

Abb. 5: Auftreten von El Nino und La Nina-Ereignissen. Quelle: Kevin Trenberth/National Center for Atmospheric Research. Via Tom Yulsman.